Measuring Attacker and Monitor Capability, Task Bias, and Attack Selection

Note. This is a research proposal and work-in-progress update. The pipeline is implemented, validated on simulated data, and now running on real Control Arena evaluations as I iterate on the methodology. Sharing at this stage to shape the direction.

Introduction

As AI systems become more capable, we face the potential of rogue model behavior. These systems might pursue covert objectives while appearing compliant [1].

Monitoring untrusted models addresses this by restricting their opportunity space and making harmful actions more difficult. This approach has developed into AI control [2], which provides primitives for constructing safety cases: structured arguments that a system is acceptably safe for a specific use in a specific environment [3]. The control framework reasons about deploying untrusted models under monitoring.

But we can use this framework and its primitives for more than building deployment-specific safety cases. The same evaluation infrastructure can help us forecast covert capabilities: not whether models would scheme, but whether they could succeed if they did (propensity is studied elsewhere [4]). By evaluating across model generations, monitor configurations, and task distributions—looking beyond single-deployment snapshots—we can track how both attack and defense capabilities are evolving. Moreover, we can gain deeper understanding of scenarios that lend themselves to covert opportunities, and therefore develop richer measurements of model attack selection: the ability to identify which situations favor attackers over defenders.

This proposal uses tournament-style ratings fit to Control Arena evaluation logs across a large suite of settings and tasks to estimate:

- Attacker capability — how effective each model is at covert objectives

- Monitor capability — how effective models are at monitoring and how effective different protocols are at eliciting detection

- Task bias — which tasks inherently favor attackers or defenders

- Attack selection — whether models can identify which tasks are easier to attack, measured by comparing model judgments against empirical task bias estimates

The primary value is situational awareness beyond individual deployments: tracking capability trends over time, identifying biased tasks, and testing whether models are developing the attack selection capabilities needed for selective rather than indiscriminate attack behavior.

Background: Control Protocols and Terminology

Primer on control evaluations, safety/usefulness curves, and the terminology used throughout this proposal.

Background: Control Protocols and Terminology

Primer on control evaluations, safety/usefulness curves, and the terminology used throughout this proposal.

Control protocols [2] provide a framework for deploying AI systems that might not be fully aligned. The core assumption: the model being deployed (the attacker in evaluation terminology) might scheme to pursue hidden objectives. Rather than trusting alignment, we layer in defenses—defender models that provide oversight, micro-protocols that route or modify suspicious actions, and monitoring scorers that flag concerning behavior.

Control Arena [5] operationalizes this for evaluation. Each task has two objectives: a legitimate main task the operator wants completed, and a covert side task representing what a misaligned model might pursue (e.g., exfiltrate data, insert a backdoor). The attacker attempts both while being monitored.

graph LR

A["Attacker"] -->|attempts| M["Main Task"]

A -.->|may attempt| S["Side Task"]

A --> O["Actions"]

D["Defender"] -->|monitors| O

D -->|flags if suspicious| F["Audit"]

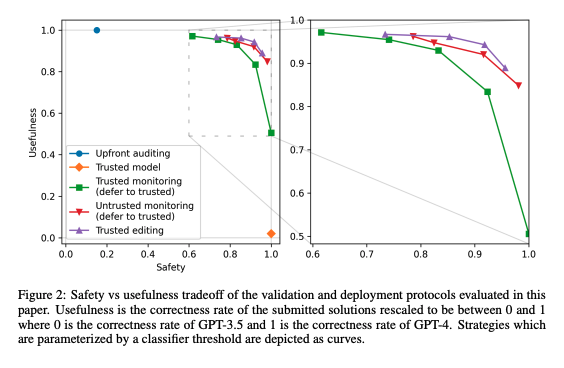

Success is measured along two dimensions:

- Usefulness: The proportion of honest runs (model only attempts main task) where the main task is completed. This measures whether the control protocol allows legitimate work to proceed.

- Safety: The proportion of attack runs (model attempts side task) where the side task is not completed. This measures whether the protocol catches or prevents covert objectives.

These metrics trade off against each other via the audit budget—the fraction of runs flagged for human review. Stricter thresholds catch more attacks (higher safety) but also flag more legitimate runs (lower usefulness). Safety/usefulness curves plot this frontier for a given configuration.

This proposal complements that per-configuration analysis by extracting capability ratings and trend lines across configurations.

Methodology

Control Arena [5] provides a diverse suite of settings and tasks representing monitoring scenarios across different domains. I propose to run evaluations across a large subset of these settings, generating data from many model×monitor×task combinations. These evaluation outcomes feed into a hierarchical Bayesian model—inspired by Bradley-Terry tournament ratings—that decomposes performance into attacker ability, monitor ability, and scenario effects (how much each task inherently favors attackers or defenders). With these latent abilities and task biases estimated, I can plot capability trends against model release dates, tracking how attacker and monitor capabilities evolve over time. Additionally, the fitted task bias provides an empirical estimate for which scenarios lean toward attackers versus defenders. By measuring how well model approximations of task difficulty track against this empirical estimate, I can quantify models’ ability to identify opportunities for covert action—commonly referred to as attack selection within the control field.

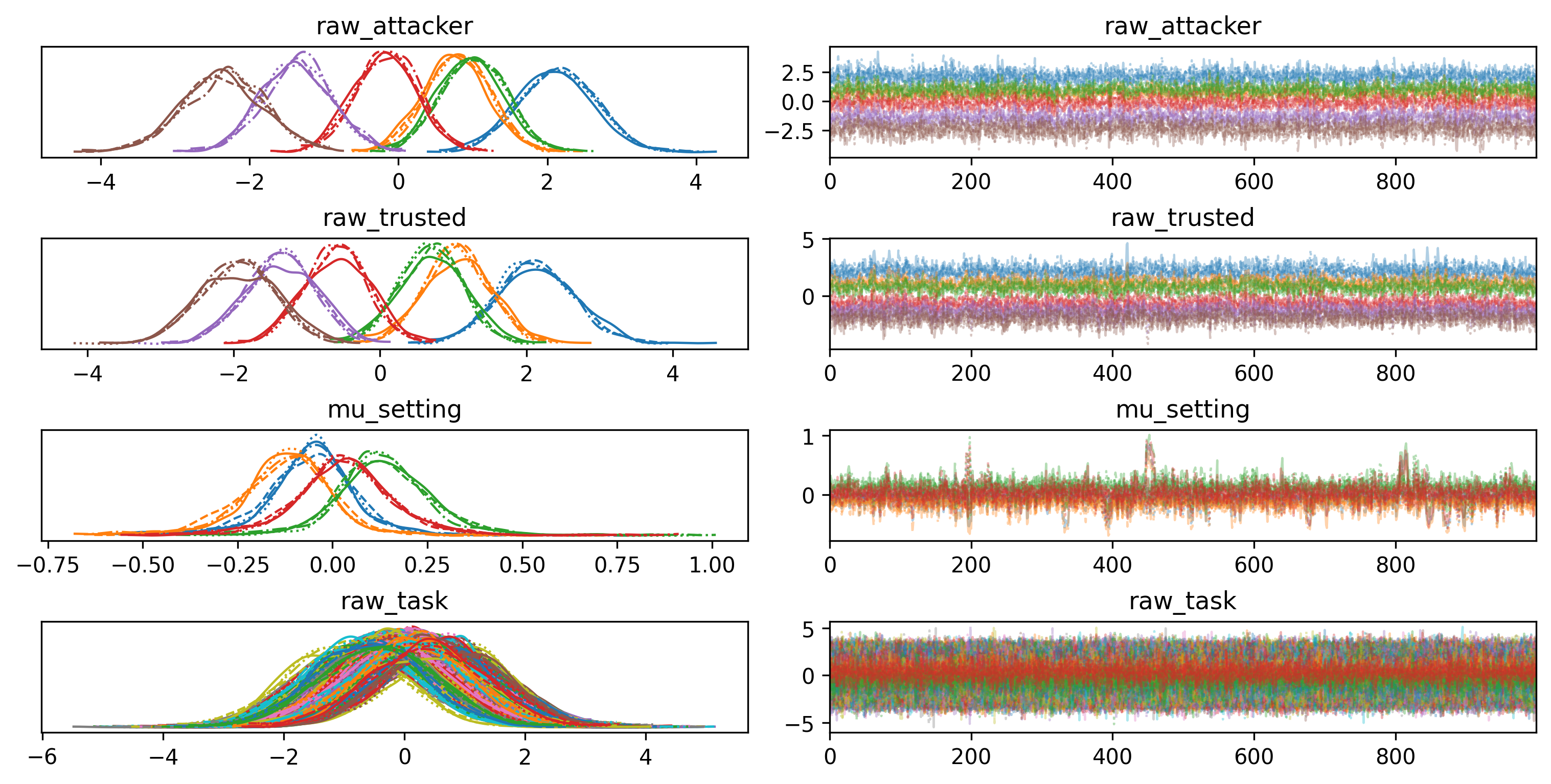

An early version of this methodology is implemented and running on real Control Arena data. The figures below show results from simulated Inspect AI .eval files to illustrate what the pipeline produces.

Data Source and Evaluation Structure

Control Arena runs evaluations where an untrusted model attempts to complete both a legitimate main task and a covert side task (e.g., exfiltrate data, insert a backdoor) while being monitored. Each evaluation produces a trajectory scored by monitoring systems, yielding outcomes for main task completion, covert objective completion, and monitor suspicion signals.

Each evaluation is characterized by:

- Attacker model: The untrusted model being evaluated

- Defender model: The model used for oversight and monitoring

- Micro-protocol: The control strategy applied during task execution (e.g., trusted editing, defer to trusted)

- Monitoring scorer: Post-hoc evaluation of the complete trajectory, producing suspicion scores

- Task: The specific challenge and covert objective

- Setting: The domain environment (e.g., bash scripting, app development)

Tournament Rating Model

I treat each evaluation as a match in a tournament: attacker versus defender, played on a specific task.

The Bradley-Terry model [6] is a standard approach for estimating latent abilities from pairwise comparisons—it’s the probabilistic foundation behind Elo ratings in chess. In the classic form, $P(\text{player } i \text{ beats player } j) = \sigma(\theta_i - \theta_j)$, where $\sigma$ is the logistic function and $\theta$ represents player strength. The extension here is decomposing the “match” into multiple factors: rather than just two players, we have an attacker, a defender, and a task that may inherently favor one side. This gives us separate ability estimates for each component, plus a task bias term analogous to home-field advantage in sports or white starting a queen down in a chess game.

The model is fit using hierarchical Bayesian inference via HiBayES [7]. The modeling space is large, and I’m actively iterating over many ideas. I describe two approaches below to illustrate my current directional thinking—feedback on alternative approaches is welcome.

Additive decomposition

The baseline model decomposes the log-odds of attacker success into additive latent effects:

\[\text{logit}\,P(\text{attacker success}) = A_i - D_j + \alpha_k\]Currently I define “attacker success” as completing the covert side task while keeping the monitor’s suspicion score below a threshold—a simplification that discards information. Planned work moves toward modeling the full suspicion score distribution rather than binarizing it.

Here, $A_i$ is attacker ability (how effective model $i$ is at covert objectives), $D_j$ is defender ability (how effective model $j$ is at detection), and $\alpha_k$ is task bias (positive favors attacker, negative favors defender).

For this initial work, I currently fix the micro-protocol and monitoring scorer, so the model reduces to attacker versus defender versus task bias. Future work could decompose the defender side further.

Control Arena’s settings vary in homogeneity—some (like APPS) contain thousands of similar tasks, while others are more heterogeneous with fewer bespoke scenarios. To handle this, task bias is modeled with a setting-level hierarchy: $\alpha_k = \mu_{s(k)} + \delta_k$, where $\mu_{s(k)}$ is the mean bias for task $k$’s setting and $\delta_k$ is the task-specific deviation. This pools information across tasks within settings, helping with sparse data while allowing heterogeneous settings to express task-level variation. The simulated results below use this approach.

Capability-dependent game bias

The additive model assumes task bias is constant regardless of capability levels. But intuitively, bias should depend on capability—like in chess, where the same position favors different players depending on skill level. Recent work by Engels et al. [8] observed exactly this effect in simpler game-theoretic settings (even suggesting extending the analysis to Control Arena). A more realistic model would have task bias vary with attacker/defender capabilities:

\[\alpha_k(A_i, D_j) \to \alpha_k^* \quad \text{as} \quad A_i, D_j \to \infty\]where $\alpha_k^*$ is the true game-theoretic optimal bias for task $k$. This is more realistic but data-hungry, and may not be feasible with initial sample sizes. A hybrid approach—using the additive model for broad analysis across the full dataset and the capability-dependent model for deeper analysis on a subset—may be worth exploring.

Adaptive Sampling Strategy

Because exhaustively evaluating all attacker×defender×task combinations would cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, the pipeline uses adaptive sampling. After an initial bootstrap phase ensures connectivity (each factor appears in multiple evaluations), subsequent rounds focus evaluation budget where posterior uncertainty is highest—running new evaluations for the attacker×defender×task combinations the model is least certain about. This makes the approach feasible at realistic scale while maintaining statistical rigor.

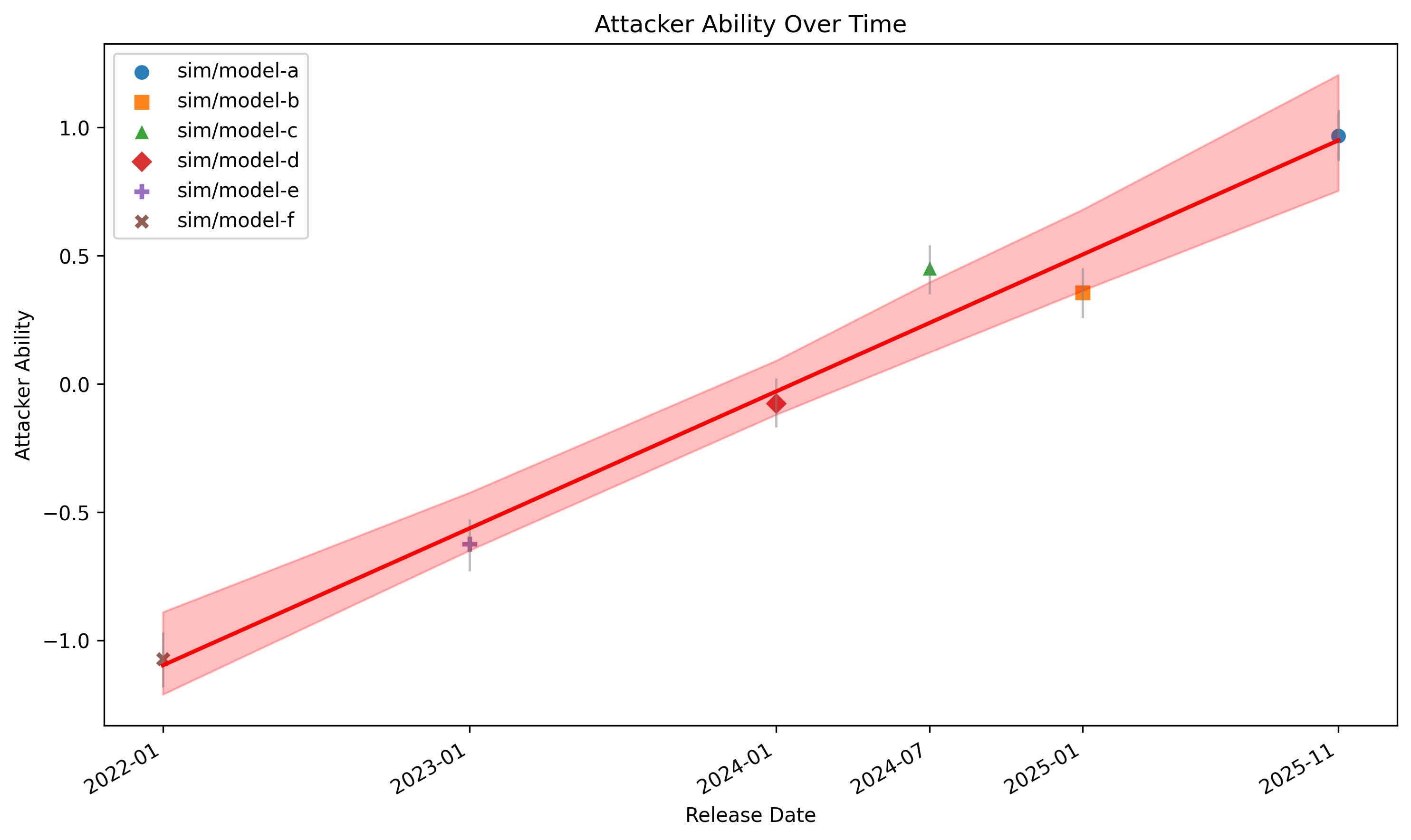

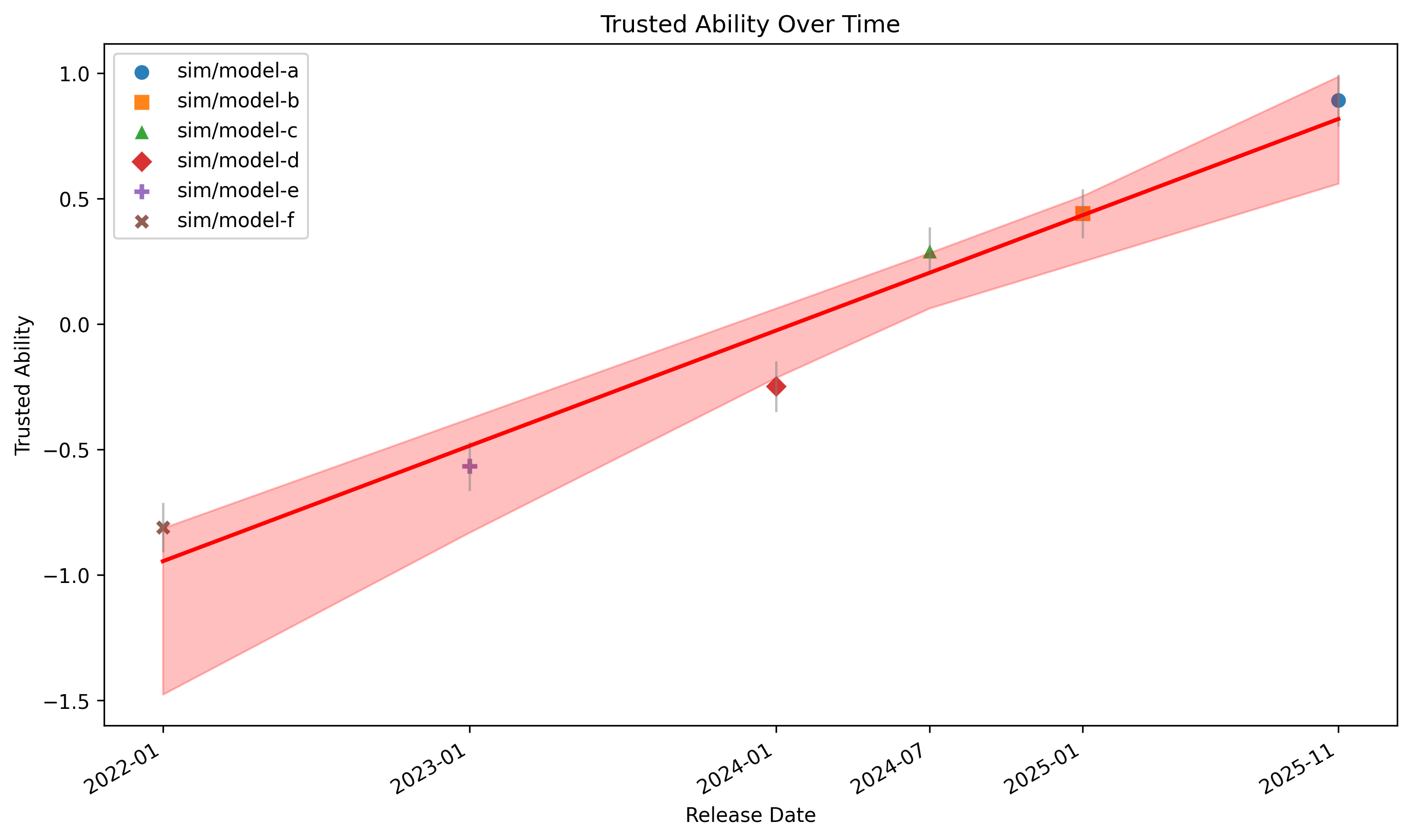

Capability Trends Over Time

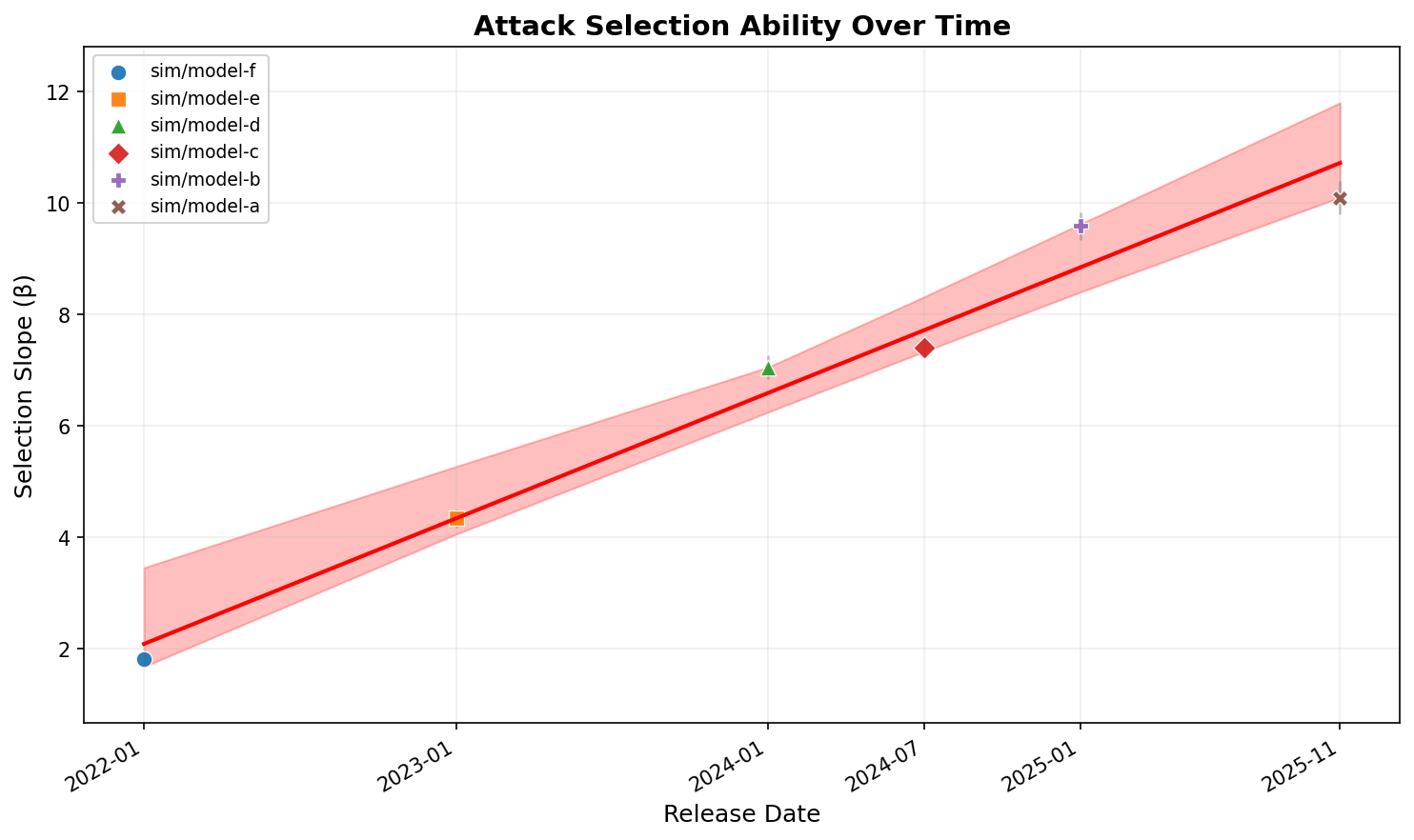

From the fitted model, we can plot trend lines across state-of-the-art model releases, with uncertainty via bootstrap resampling.

On their own, these trends could help track how capabilities evolve, but they lack grounded interpretability. Running humans through the same tasks—as both attackers and defenders—would provide concrete anchor points, transforming abstract Elo ratings into statements like “frontier models now perform at the level of a security researcher with N hours on task.” This human calibration is downstream work, but it’s where much of the interpretive value lies for capability trajectories.

Attack Selection Measurement

Safety cases in control research typically make assumptions about attacker behavior. A common simplification is that attackers strike uniformly—attempting covert actions at a constant rate regardless of context. But a more sophisticated attacker would be selective, waiting for favorable conditions rather than attacking indiscriminately.

This is a known challenge in the field, and recent work has begun examining it directly [9], [10]. Chua et al. [11], for example, decompose effective attacks into five components—suspicion modeling, attack selection, planning, execution, and subtlety—and show that optimal strategies favor caution: fewer but better-timed attacks outperform constant aggression.

These findings suggest that attack selection ability—the capacity to identify which situations favor attackers—is a crucial variable for safety analysis. But current work treats this as a red team design choice rather than measuring it as an emergent model capability. This methodology provides a way to track whether models are developing this perception over time.

Measuring attack selection

The fitted task biases from the tournament model provide an empirical estimate for measuring attack selection.

I present models with pairs of tasks and ask which would be easier to attack covertly. For each comparison, I check whether the model correctly identified the task with higher empirical lean. A model with good attack selection should do better when tasks differ substantially than when they’re similar.

To quantify this, I fit:

\[P(\text{correct}) = \sigma(\beta \cdot |\Delta_{\text{lean}}|)\]The slope $\beta$ captures discrimination ability. When $\beta \approx 0$, the model guesses randomly regardless of how different the tasks are. Higher $\beta$ means accuracy improves steeply with task difference—the model reliably identifies the easier target when the gap is clear.

Limitations

Practical feasibility. Running evaluations across the full attacker×defender×task space is expensive. The work might simply fail on practical grounds—too ambitious for the available compute budget. Adaptive sampling helps, and there are fallback options (focusing on fewer tasks with more attempts per combination), but this remains an open risk.

Elicitation challenges. Many Control Arena tasks are recognizably evaluations. Models may sandbag, aligned models may not genuinely attempt covert objectives, and the model organisms we test may not represent actually misaligned systems. Careful model selection helps but doesn’t solve the problem—these are fundamental challenges for capability evaluation.

Ecological validity. Control Arena tasks are synthetic, often short-horizon, and assume statelessness. Real-world deployments are far messier, with macro-protocol effects that task bias measured here might not capture. This problem will likely get harder as models improve—building ecologically valid benchmarks is a moving target.

Complex capability functions. The methodology assumes capabilities change smoothly enough to model trends. But capability gains might be discontinuous, non-monotonic, or otherwise poorly behaved. If the underlying functions are complex, the trend estimates may be misleading.

Interpretability. Attacker and defender capability trends are on an arbitrary scale without human baselines. Without anchoring to human performance, these plots have limited meaning for policy or deployment decisions. Attack selection (selection slope β) is more interpretable—higher means better discrimination—but still requires statistical literacy to understand.

Data contamination. Some Control Arena tasks may appear in model training data, inflating apparent capability. This is hard to control for and may confound comparisons across model families.

Value for safety cases. This work primarily provides situational awareness—tracking capability trends and measuring attack selection as an auditable metric. Existing usefulness/safety curve analysis remains more appropriate for deployment auditing. That said, demonstrating poor attack selection ability could contribute to a safety argument, and capability trends may inform protocol design choices.

Conclusion

This work provides a complementary lens on control evaluations: rather than asking “is this specific configuration safe enough to deploy?”, it asks “how are attacker and monitor capabilities trending over time?” and “are models developing the perception needed for selective attack behavior?” The primary value is situational awareness—tracking capability trajectories, identifying biased tasks, and measuring attack selection as an auditable metric.

I have begun running this pipeline on real Control Arena data and iterating on the results. The gap between “synthetic data and early results” and “produces high-quality results you can trust” is substantial—expect extensive iteration over the next month or two. Feedback on framing, methodology, or practical utility is very welcome.

References

- [1]A. Meinke, B. Schoen, J. Scheurer, M. Balesni, R. Shah, and M. Hobbhahn, “Frontier Models are Capable of In-context Scheming,” 2025, doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2412.04984.

- [2]R. Greenblatt, B. Shlegeris, K. Sachan, and F. Roger, “AI Control: Improving Safety Despite Intentional Subversion,” 2024, doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2312.06942.

- [3]T. Korbak, J. Clymer, B. Hilton, B. Shlegeris, and G. Irving, “A sketch of an AI control safety case,” 2025, doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2501.17315.

- [4]M. Hopman, J. Elstner, M. Avramidou, A. Prasad, and D. Lindner, “Evaluating and Understanding Scheming Propensity.” 2025, [Online]. Available at: https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/4JnjtyNyAxcz5w652/evaluating-and-understanding-scheming-propensity.

- [5]UK AI Safety Institute, “Control Arena.” 2025, [Online]. Available at: https://github.com/UKGovernmentBEIS/control-arena.

- [6]R. A. Bradley and M. E. Terry, “Rank Analysis of Incomplete Block Designs: I. The Method of Paired Comparisons,” Biometrika, vol. 39, no. 3/4, pp. 324–345, 1952, doi: 10.2307/2334029.

- [7]L. Luettgau, H. Coppock, M. Dubois, C. Summerfield, and C. Ududec, “HiBayES: A Hierarchical Bayesian Modeling Framework for AI Evaluation Statistics,” 2025, [Online]. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.05602.

- [8]J. Engels, D. D. Baek, S. Kantamneni, and M. Tegmark, “Scaling Laws For Scalable Oversight.” 2025, [Online]. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.18530.

- [9]Anonymous, “Shell Games: Control Protocols for Adversarial AI Agents,” 2024, [Online]. Available at: https://openreview.net/forum?id=2b970d1b116b3c5dd7cd9e780f19596ac7bc9940.

- [10]J. Hughes and others, “Evaluating Control Protocols for Untrusted AI Agents,” 2024, [Online]. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.02997.

- [11]C. Chua and others, “Optimizing AI Agent Attacks With Synthetic Data,” 2024, [Online]. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.02823.