Extending the Cyber Task Horizon Study

Note. Jack Payne and I are reviving and extending work I shared in June. I'm posting this update to gather feedback at upcoming AI safety events.

Our Prior Research

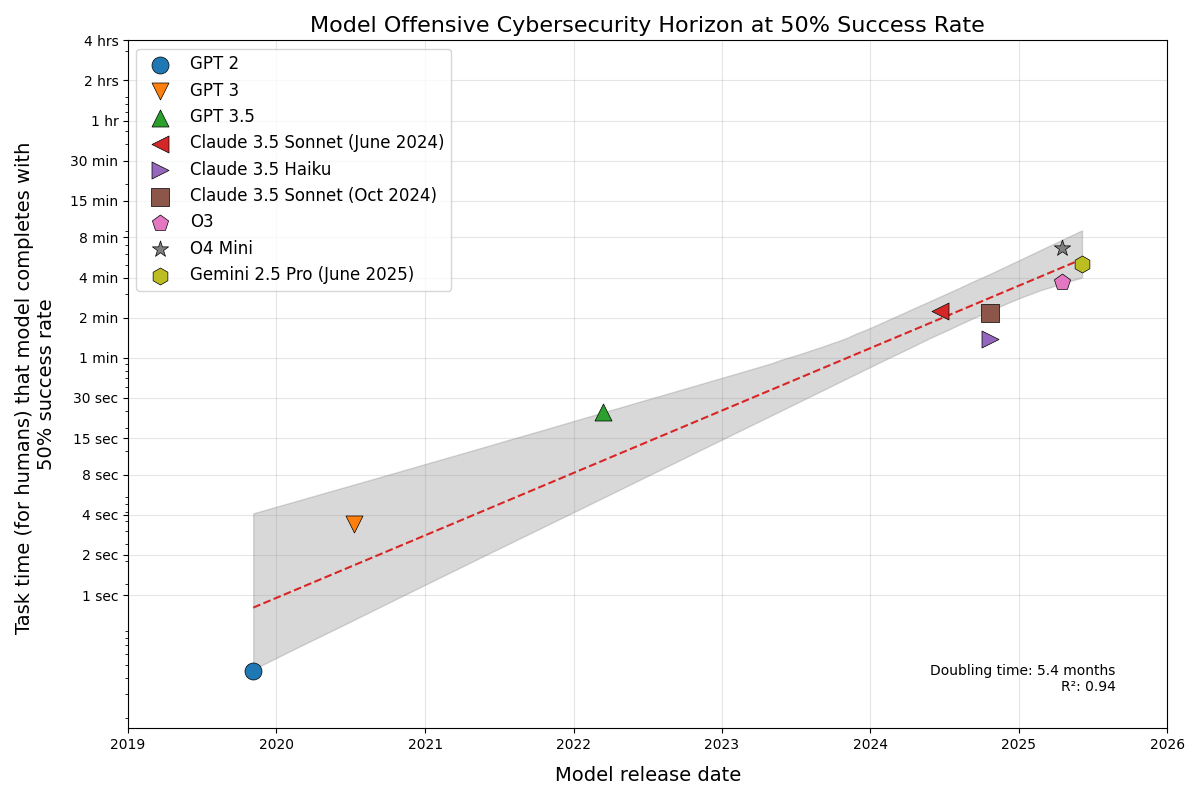

In June I measured how long offensive cybersecurity tasks AI models could reliably complete [1]. Borrowing METR’s methodology [2], I used human task time as a proxy for difficulty, fit IRT curves across five benchmarks, and read off capability horizons. The headline findings: a roughly 5-month doubling time, and a 6-minute P50 horizon for the best models at the time.

The work had clear limitations. Evaluations were single-shot. Human time estimates leaned heavily on AI assistance rather than professional baselines. And three of the five benchmarks were CTF competitions—meaning 100% of the longer-horizon data came from a task format that, while useful, is only a narrow slice of real offensive work.

Since Then

In the interim, the pace of progress in this domain has been remarkable.

Capability gains

Anthropic’s Opus 4.5 system card [3] reports ~0.82 pass@1 on their CyBench subset [4]—a frontier model now one-shots the large majority of professional-level CTF challenges under their setup. Sonnet 4.5 roughly doubled CyBench performance compared to 3.x within six months [5]. OpenAI’s GPT-5.1-Codex-Max [6] hits 80% pass@1 on CVE-Bench [7] and 76% on their internal CTF benchmark—up from 40% and 27% respectively when GPT-5 launched in August.

Real-world impact

In November, Anthropic disclosed that a Chinese state-sponsored group used Claude Code as the engine of a multi-target espionage campaign [8]. By their estimate, the AI executed 80–90% of tactical operations—recon, exploit development, lateral movement, exfiltration—across roughly 30 targets. In August, they documented a “vibe-hacking” extortion campaign where a low-skill actor used Claude to compromise at least 17 organizations, handling everything from credential harvesting to ransom note generation [9].

These aren’t hypothetical risks. They’re real-world incidents. And they map surprisingly well onto the “short-horizon, brittle but improving” picture the June study suggested.

What we’re doing

Jack is leading the extension, addressing the study’s main limitations:

- Broader task coverage. Adding CVE-Bench [7] and CyberGym [10] to move beyond CTF-only long-horizon data. Real vulnerabilities in real codebases, not just competition puzzles.

- More models. Sonnet 4.5, Opus 4.5, latest GPT and Gemini releases, and as many others as budget allows—including models we couldn’t afford in June.

- Multiple runs. 3–5 seeds per task-model pair instead of single shots, to reduce variance in the IRT fits.

- Professional time estimates. Paying a security expert for grounded task-time estimates, reconciled against first-blood data where available.

- Evaluation robustness. Continued work on prompts, elicitation, log review, and grading to ensure models get a fair opportunity to succeed.

As a stretch goal, we want to probe scaffolded agents—Claude Code style setups, specialized appsec tools—to see how far horizons shift with better tooling.

Why this matters

The point of horizon plots isn’t to produce definitive risk verdicts. It’s legibility.

You can tell a policymaker “current models can sustain a 6-minute offensive task half the time” and they understand what that means. If horizons double every 5 months, you can start asking concrete questions: what would it take to reach hour-long intrusion chains? Day-long ones? Those questions have concrete implications for defense investment, disclosure timelines, and threat modeling.

Horizon plots won’t answer them definitively, but they give policymakers and funders a grounded trendline to anchor the conversation—something richer benchmarks like CyberGym [10] can then fill in with granular detail.

We’re aiming to have updated results early next year. If you have pointers to a security professional for estimation work, feedback from a cybersecurity or evaluation science perspective, or thoughts from a governance angle on what would make this most useful for policymakers, we’d love to hear from you!

References

- [1]S. Peters, “AI Task Length Horizons in Offensive Cybersecurity.” 2025, [Online]. Available at: https://sean-peters-au.github.io/2025/07/02/ai-task-length-horizons-in-offensive-cybersecurity.html.

- [2]METR, “Measuring AI Ability to Complete Long Tasks,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.13547, 2024.

- [3]Anthropic, “System Card: Claude Opus 4.5.” Anthropic PBC, Nov. 2025, [Online]. Available at: https://assets.anthropic.com/m/64823ba7485345a7/Claude-Opus-4-5-System-Card.pdf.

- [4]A. K. Zhang et al., “Cybench: A Framework for Evaluating Cybersecurity Capabilities and Risks of Language Models,” 2025, [Online]. Available at: https://openreview.net/forum?id=tc90LV0yRL.

- [5]Anthropic, “System Card: Claude Sonnet 4.5.” Anthropic PBC, Sep. 2025, [Online]. Available at: https://assets.anthropic.com/m/12f214efcc2f457a/original/Claude-Sonnet-4-5-System-Card.pdf.

- [6]OpenAI, “GPT-5.1-Codex-Max System Card.” OpenAI, Nov. 2025, [Online]. Available at: https://openai.com/index/gpt-5-1-codex-max-system-card/.

- [7]Y. Zhu et al., “CVE-Bench: A Benchmark for AI Agents’ Ability to Exploit Real-World Web Application Vulnerabilities,” 2025, [Online]. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.17332.

- [8]Anthropic, “Disrupting a covert influence operation targeting AI-assisted coding.” Anthropic PBC, Nov. 2025, [Online]. Available at: https://www.anthropic.com/news/disrupting-AI-espionage.

- [9]Anthropic, “Detecting and countering malicious uses of Claude: August 2025.” Anthropic PBC, Aug. 2025, [Online]. Available at: https://www.anthropic.com/news/detecting-countering-misuse-aug-2025.

- [10]Z. Wang, T. Shi, J. He, M. Cai, J. Zhang, and D. Song, “CyberGym: Evaluating AI Agents’ Real-World Cybersecurity Capabilities at Scale,” 2025, [Online]. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.02548.